by Yawen Zheng

“Weak, selfish, irrational, impulsive, mentally ill” – it is not uncommon to come across such words used to describe people who have thought about or attempted suicide. The stigma around suicide has persisted for a long time. Yet it is worth pausing to consider why this stigma continues. Often, this comes from a lack of understanding, as well as from historical and religious influences that frame suicide as a perceived loss of “humanness”.

Indeed, suicide may appear to go against the basic human survival instinct, leaving those bereaved desperately wondering why their loss occurred. Decades of research has illuminated the suicidal mind – revealing a complex interplay of biopsychosocial factors that can lead to emotional, cognitive, and behavioural dysregulation. This article therefore explores suicide risk through the lens of self-regulation, a process fundamental to being human.

What Is Suicide?

While definitions of suicide vary across disciplines, they generally share four core elements: that death is viewed as a behavioural outcome, that it is self-inflicted, that it reflects a desire to change one’s circumstances through death, and that the individual possesses conscious awareness of the act. Each of these elements highlights the complex psychological process underlying suicide, reflecting both a person’s capacity for suicide, and at times, their struggle for self-control and adaptive coping.

What Is Self-Regulation?

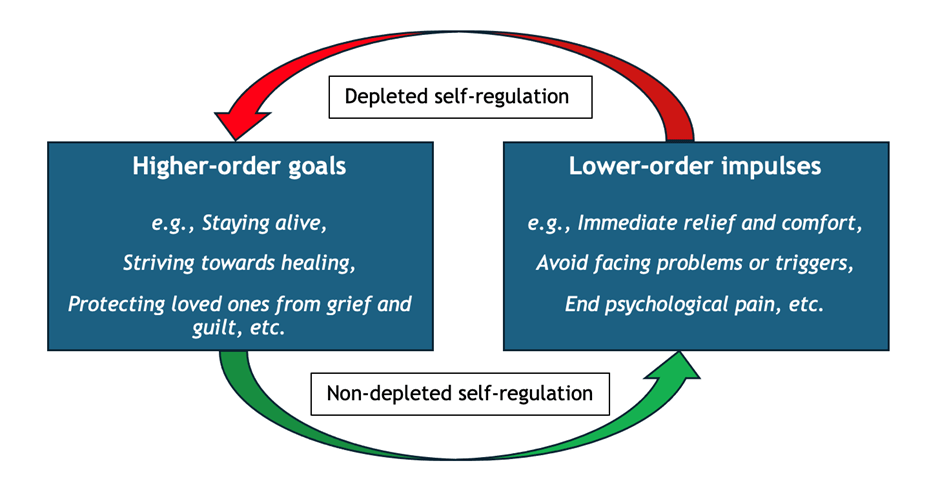

Self-regulation broadly refers to the ability to control thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, where higher-order goals (e.g., long-term goals) guide and override lower-order impulses and reactions (e.g., momentary urges). It involves three key components:

Standards: The ideals or goals that define how things should be.

Monitoring: Assessing how things are by comparing one’s actual state to standards.

Operating: Taking control of oneself to change the current state when things do not match expectations.

The Strength Model is a framework which posits that our capacity to self-regulate draws on a limited pool of mental resources which can be exhausted; much like a muscle that becomes fatigued after excessive use. When these resources are depleted, individuals experience reduced self-control, making them more vulnerable to impulses and less capable of achieving their broader goals (a state referred to as ego depletion). Ego-depletion is characterised by mental passivity – a tendency to avoid effortful activities in favour of less demanding alternative behaviours. Failures of self-regulation occur when lower-order impulses override higher-order goals. These failures generally take two forms:

Underregulation: The inability to exert self-control.

Misregulation: Self-control is exerted in a way that fails to achieve the desired outcome.

Suicide and Self-Regulation

Individuals at risk of suicide may experience stronger desires and more unresolved inner conflicts than those who are not suicidal, often due to accumulating emotional distress and a significant discrepancy between their current reality and personal standards. Managing this inner conflict requires a lot of self-regulatory effort, which can leave individuals feeling mentally exhausted. When mental resources are diminished, the self-regulation process can reverse, allowing lower-order impulses to override higher-order goals (see illustration below). This phenomenon represents a failure of Transcendence – the inability to focus or divert attention beyond immediate stimuli – which is a proximal cause of self-regulation failure. This state closely resembles the “tunnel vision” commonly observed in suicidal individuals, characterised by a narrowing thought process evoked by feelings of entrapment and hopelessness.

Illustration of a proposed self-regulation process among individuals at risk of suicide, with the dominance of processes (indicated by the arrow) varying according to the state of self-regulation

The following sections discuss how the process of self-regulation relates to suicide risk through two assumptions.

I – Suicide as self-regulation to manage overwhelming negative emotions and life stressors

Research shows that, for some individuals, thoughts of suicide can serve as a way to cope with intense emotional pain, providing a temporary sense of comfort and control over their life. In this sense, suicidal thoughts may function as a form of self-regulation – a way to manage unbearable feelings. But not all types of suicidal thoughts work in the same way. This pattern is more common in passive thoughts (e.g., “If I want, I could kill myself”) than in thoughts driven by fear and loss of control (e.g., “I’m afraid of what I might do to myself”).

Even though suicidal thoughts may bring short-term relief, they do not reduce suicide risk. Over time, people can become caught in a cycle where these thoughts reoccur because of the temporary ease or solace that they provide – this is known as negative reinforcement. This paradoxical effect can therefore be understood as misregulation – in which an individual’s attempt to cope ultimately fails to improve psychological well-being.

II – Suicide as a result of self-regulation failure

As mentioned earlier, the Strength Model of self-control suggests that our self-regulation ability works like a muscle – it can become exhausted after too much use. When combined with the Escape Model of Suicide, these frameworks can help to explain how suicidal behaviour can emerge as a result of the gradual depletion of self-regulatory resources. When individuals experience ongoing stress and emotional pain arising from the perceived gap between how their life actually is and how they wish it was, substantial self-regulatory resources are needed to function day-to-day.

Over time, this constant battling can deplete individuals’ mental resources, making them more vulnerable to entering a state of emotional numbness (i.e., cognitive deconstruction) as a means of escaping painful feelings when experience extreme distress. Eventually, suicide may be perceived as the only escape from feelings of entrapment and hopelessness. This is an example of underregulation – when a person’s ability to manage thoughts and feelings breaks down after being pushed too far for so long.

Summary

Suicidal thoughts and feelings may reflect deep emotional exhaustion, which can fluctuate with life’s challenges and the strength of our self-regulatory resources. Our ability to use self-control is one of the few characteristics that makes us uniquely human. Looking at suicide through this lens can help us to understand that it is not simply about something fundamentally “wrong” with a person, but more about how human coping systems can become overwhelmed. Many myths of suicide still exist, making it seems mysterious or impossible to understand. But when we see it as part of the human struggle, it becomes clearer and appeals to our compassion. But that does not mean that it is inevitable. When what we once valued – self-awareness, connection, and hope – begin to crumble and stretches our mental resources to their limits, for some, suicide tragically reflects the very aspects of our humanity that we cannot better live without. As a society, we need to do more to ensure that every one of us feels valued. To this end, we all have a role to play in suicide prevention.

You must be logged in to post a comment.