Suicide rates for both men and women peak in mid-life (Office for National Statistics, 2024), and for women, the highest rates are among those aged 45–54. This makes mid-life a critical time for addressing suicide risk.

We often hear that men are more likely to die by suicide, but women are more likely to attempt suicide or engage in non-suicidal self-injury (Canetto & Sakinofsky, 1998). In England, the latest Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey (APMS; Morris et al., 2025) found that more women reported a lifetime suicide attempt (8.6% vs. 6.9%) or non-suicidal self-injury (12.6% vs. 8.5%) compared with men.

A range of factors may contribute to this risk for women in mid-life — things like financial stress, bereavement, alcohol use, divorce, and physical or mental illness (Qin et al., 2022; Clements et al., 2025). Despite the overlap between these established risk factors and major hormonal and psychological shifts that occur during menopause, surprisingly little high-quality research has explored how this transition might influence suicide risk (Martin-Key et al., 2024; Hendriks et al., 2025).

What is menopause?

Menopause is defined as having no menstrual periods for 12 consecutive months (NICE, 2025). It’s a natural stage of life that marks the end of menstruation and fertility, usually occurring between ages 45 and 55, with the average in the UK being 51 (NHS, 2022).

Before menopause, there’s the perimenopause — a transition period when hormone levels fluctuate and menstrual cycles become irregular. This happens because the ovaries gradually produce less oestrogen and progesterone (NICE, 2025). These hormonal ups and downs can trigger a mix of physical and emotional symptoms, including hot flushes, sleep problems, brain fog, heart palpitations, and changes in mood or irritability.

Research shows that perimenopause can significantly affect mental health, increasing the likelihood of anxiety and depression (Alblooshi et al., 2023), and conditions like bipolar disorder (Shitomi-Jones et al., 2024). There’s also evidence of a rise in psychiatric admissions during this time (Reilly et al., 2020). Hormonal changes affecting brain regions involved in mood and neurotransmitter regulation may help explain this vulnerability (Albert & Newhouse, 2022).

What do we know about suicide risk during menopause?

A number of reviews have looked at this topic — and most highlight big gaps, and methodological issues, in the evidence (Martin-Key et al., 2024; Hendriks et al., 2025).

For example, Martin-Key et al. (2024) found mixed results on whether suicide risk changes across menopause stages, but many studies relied on limited designs (like case studies or cross-sectional data) or used age as a rough substitute for menopause status.

Hendriks and colleagues (2025) focused on higher-quality studies and found that 84% (16 out of 19) showed some link between menopause and increased suicidality. Nearly half of the studies reported higher suicide risk during the perimenopausal stage, with hormonal fluctuations, existing mental health problems, physical symptoms, and poor social support emerging as key factors. However, the authors noted that findings were still limited by study quality and consistency.

Looking at specific data, Usall et al. (2009) found that perimenopausal women were seven times more likely to report suicidal thoughts (7.8%) compared with pre- (1.1%) or postmenopausal (1.0%) women. More recently, Hendriks et al. (2024) found that 16% of women attending a specialist menopause clinic reported suicidal ideation or self-harm thoughts in the two weeks before their appointment.

Together, these studies suggest that perimenopause may be a particularly vulnerable time — but more robust, long-term research is needed to understand exactly who is at risk and why.

Understanding suicide risk during menopause

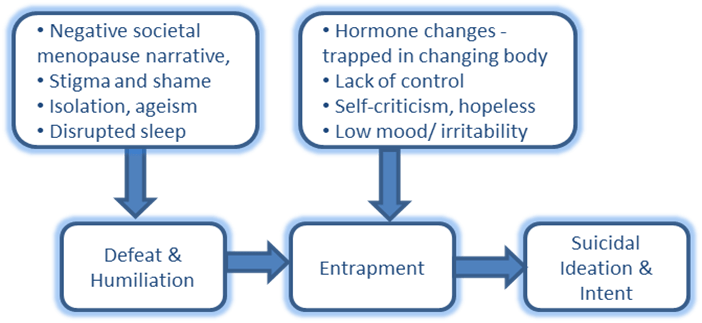

To make sense of suicidal thoughts and behaviour during menopause, and guide intervention efforts, it can help to use an existing framework like the Integrated Motivational–Volitional (IMV) model of suicidal behaviour (O’Connor & Kirtley, 2018). An example of the motivational phase of the model adapted for menopausal risk factors is outlined below.

The IMV model proposes that feelings of defeat and entrapment play a central role in the development of suicidal thoughts. When applied to menopause, the model helps show how hormonal, psychological, and social changes could contribute to these feelings. Supporting this, a recent qualitative study found that hopelessness and entrapment were key triggers for suicidal thinking among menopausal women (Hendriks et al., 2025).

The motivational phase of the IMV model of suicidal behaviour (O’Connor and Kirtley, 2018) adapted for menopausal suicide risk

What needs to change?

There’s growing recognition that menopause — and the menstrual cycle more broadly — needs to be part of how we assess and support mental health (Delanerolle et al., 2025; Marwick et al., 2025; Vollmar et al., 2025).

Delanerolle et al. (2025) argue that mental health considerations should be a core part of menopause care, while others suggest treating the menstrual cycle as a “vital sign” in psychiatry and health services (Marwick et al., 2025; Vollmar et al., 2025), since tracking it can offer important clues about both physical and mental wellbeing.

Certainly, it is clear menopause and mental health require more awareness and focus within healthcare settings (Hendriks et al., 2025a). This is especially true for GPs and primary care, where key opportunities for support are often missed, as menopausal women often do not link their mood with menopause, and stigma maybe a further barrier (Burgin et al., 2025).

Future studies need to dig deeper into how menopausal symptoms and hormonal changes relate to suicide risk, while also considering the social and cultural factors that shape how women experience this transition. Our understanding of menopause and suicide risk is still limited — and greater recognition, research, and open conversation are urgently needed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.